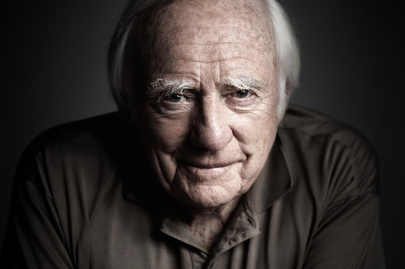

The Peter Appleyard Interview

Peter Appleyard has played with some of the best,

including Benny Goodman.

Lost tapes, espionage, adultery and drumicide?? Vibraphonist Peter Appleyard talks about a long life in music and the release of a CD that had been shelved for nearly 40 years.

I don’t recall when I first saw Peter Appleyard play the vibes on television, but it had to be in the 1960s. Needless to say, I was into popular music of the day and none of those bands included the vibes. A few years ago Toronto chanteuse Carol McCartney got Peter to appear on her CD A Night in Tunisia. She jogged my memory as to who he was. Soon after I found a copy of Peter Appleyard’s Great Vibes with Strings and I have been playing it quite frequently ever since. The vibes are an unusual instrument, as I explained (Catching the Vibe: Matthias Lupri) in earshot-online.com back in December 2006. Fast forward to 2012 and Peter Appleyard has released a CD that was recorded in 1974 with some of the finest jazz musicians alive at the time. How did this happen, why did it take so long to come out?

My mind was full of questions, but I was a little intimidated by his legendary status. After all, he is nearing his 84th birthday and he has received many honours including the Order of Canada, The Satcho Award, an honourary Doctorate and has appeared on many American and Canadian television shows over the years. He has made countless stage and recording appearances with some of the greatest jazz and popular musicians of the day. He was part of Benny Goodman’s touring band. I have also found that some elder interviewees do not suffer interviewer fools gladly. I had some trepidation.

The interview—easiest one I ever did. Mr. Appleyard is a real gentleman and does not need to be prompted. He answered all my questions in detail and even hummed and sang a bit to help me understand what he was talking about. The “new CD” Peter Appleyard and the Jazz Giants The Lost Sessions 1974 is simply amazing. As a bonus it includes a 25 minute track, which is really a piece of music history. Appleyard, now in his ninth  Mendelssohn offered me 17 pounds a week to be the percussionist for the first orchestra that appeared on British television, with a six month contract. Guess what I did?

Mendelssohn offered me 17 pounds a week to be the percussionist for the first orchestra that appeared on British television, with a six month contract. Guess what I did? decade, truly is a national treasure and he continues to record and tour.

decade, truly is a national treasure and he continues to record and tour.

JD: I’m going to take you way back. What got you into music in the first place?

PA: Well, it’s rather an odd story. Have you got time (laughs)? During the Second World War I was fiddling around with a drum set—entertaining troops—and at the time I was an apprentice compass adjustor—nautical instrument maker. In those days to go to a secondary or high school, one had to pay in England and my parents were a victim of the war and one thing and another, so they didn’t have any money so they acquired me an apprenticeship, which was a good thing to do for a young guy in that area because it was one of the largest commercial fishing ports in the world. There was a lot of maritime business.

Anyway, one of my errands that I had to do was go to the Admiralty and acquire charts for the British Navy to circumvent mine fields on the River Humber, where I lived, so they could get out to the North Sea. This half an hour’s errand used to be an hours adventure for me, because I used to stop at a record shop along the way and listen to records, which you could in those days. They were those 78 things, you know. Here I am listening to records in this booth that had a little window and meantimes the Royal Navy is waiting to go to sea (laughs). Amazing we won the war (laughs). Anyway this face appeared at the window and opened the door and said, “Hey, old chap, do you play the drums?” I said, “I do.” I was only sixteen or seventeen, then. He said, “Our drummer, last night, got caught in bed with another woman by his wife and she promptly took the fire axe off the wall and chopped up his drums.” (In those days you couldn’t buy drums) “If you’d like to come down and audition for Felix Mendelssohn’s Hawaiian Serenaders, we’re appearing at The Palace Theatre and if you’d like to come down on Saturday morning and audition for the job, because the drummer had to leave. No drums.” I went down to his audition and passed the audition and I was making 7 shillings and 6 pence, which was in those days a dollar and a half as an apprentice compass adjuster and Mr. Mendelssohn offered me 17 pounds a week to be the percussionist for the first orchestra that appeared on British television, with a six month contract. Guess what I did? That’s what really started me professionally in music and it went on from there.

JD: That’s an interesting story, but more importantly, we did win the war, right?

PA: Oh, yeah we did (laughs).

JD: So from drums you got into the instrument that you are well known for, the vibes (vibraphone). Maybe you could tell us how you got into the vibes.

PA: Well I was entertaining troops at various places during this period of time. Well, one night while I was at Stickler Aerodrome, Royal Air Force, this guy came out with a very tiny vibraphone. I don’t know how he did it, but he had several plectrums on a small wheel inside a flatbed guitar with an electric motor hitting one string that went “blrrrrrrr” and took a steel, like you would do a Hawaiian guitar, and slid it up and down the single string and plucked out a melody and with the right hand he played arpeggio de chord, open chord “da da de da”—you know, sustained it with the vibraphone. Anyway I went up to him after and said, “I like the sound of the vibes. I’ve never seen one before. May I try it?” So he said, “Go ahead.” I tried it and I said, “I really like that.” There was a cute girl standing by and she said, “Hey, you sound good on that.” I though, ahaw, maybe this is what I should be really playing (laughs); but, basically no. I asked him to sell it and he said he wouldn’t.

Anyway the war ended and later a knock came at my door and it was this little man. He asked if I still wanted to buy the vibes and I said ya. He said 15 pounds and I was making 7 and 6 a week then. Anyway I borrowed the money and my father was furious. Eventually everything worked out and I got the vibes and so and so. About ten years ago I went back to England and went to look up this little, old man. He said, “I can tell you something now that I couldn’t have told you before. Remember when we used to go to those Air Force camps, well you probably remember I never came home with you.”

I said, “Gee, that’s a long time ago, but now that you mention it, ya.” He said, “The vibes were a cover for me. I was a British spy and they had to fly me off in a single engine aircraft behind the German lines in France, prior to the invasion, and I’d meet with the French Resistance and get all kinds of information from them.” I said, “Goodness, gracious how many time did you do that?” Because as you know, if you are caught doing that you are shot immediately. “He said, “Over a dozen times.” So that’s how I started playing the vibes.

JD: Wow, that’s just amazing!”

PA: Quite a story, huh?

JD: It is quite a story. Well Peter, I think the vibes have been good for you and you have been good for the vibes.

PA: I thank you.

JD: Your were probably the first person that I saw playing the vibes and that was on tv of course, but unfortunately I haven’t had a chance to see you live.

PA: You still don’t see many of them around.

JD: There’s a few more now. There’s a young man out of Chicago named Jason Adasiewicz and a guy a bit older named Joe Locke. I’m not sure where he’s from, but I think he’s living in California, these days.

PA: He’s a great player.

JD: There’s also a fellow in Berklee named Matthias Lupri, who calls Canada home. He’s from Germany, but lived in the prairies for a long time and he’s actually pretty good, too.

PA: That’s encouraging to hear. Unfortunately there are a few problems playing vibes. First of all you have to buy one and if you don’t get a second hand one you have to start out at least at $5000-$7,000. Then, they weigh 200 pounds so you have to be in good shape to lug them around and then again, you have to buy a car or a van that will take them.

JD: Ya, I can where people would consider getting something smaller to deal with. Now, there were some famous vibes players from the old days, like Red Norvo, Milt Jackson, and Lionel Hampton. Do you find that you were influenced by any of these people?

PA: Oh, of course. There was nobody to teach me, so I taught myself to play. In England at that point where I was just playing drums, I was listening to the Benny Goodman Quartet and Sextet and I loved the sound of the instrument. That was played by Lionel Hampton, at that time. Then some time later on in 1946, I think it was, I was walking through a Woolworth’s store and I heard this record with this wonderful vibraphone player with Benny Goodman and it was Red Norvo. Also, there was a bassist on the record named Slam Stewart who is on that recent record of ours, The Lost 74 Sessions, so I had the opportunity to meet Slam and play with him and of course, I played with Benny Goodman for eight years.

JD: That is so cool. You are basically a fan of someone and later on you get to be in his band. What was Benny Goodman like?

PA: He was almost like a father to me. I used to stay in his house in New York. He had a penthouse on 66th Street and 2nd Avenue. Occasionally I’d go up to Connecticut with him to his other place. He had a farm, there. He was the most encouraging and one of the most generous people that I ever worked for. Not with salaries to play. He was very close to the numbers with his payment for playing, but he would take me out quite frequently for dinner and as I say, I stayed at his house when I was playing in New York with him as I did several times. When he was sick he would call me from wherever he was to take over the band and he was very encouraging. It was basically through his groups that I started playing and on one occasion he came up to Canada and I made all the transportation arrangements for him and accommodation and everything else. A month or so later we were playing in Ames, Iowa to about six thousand people in a huge sports arena with the sextet. We went out to eat afterwards and he put his hand in his pocket and brought out a little jewellery box. He gave me it. “What is this Benny?” He said, “This is for your hospitality in Toronto.” It was the most beautiful pair of solid gold nugget cufflinks, which I had appraised at Tiffany’s where they were made and they said a pair like that today would be close to $5,000.

JD: Wow!

PA: That’s how he was with me, but he could be very demanding. He was a perfectionist and he didn’t suffer musical fools gladly. Because of his temperament he had a terrible stare which was called “the ray.” I’ve seen him actually make musicians faint. Fortunately I never go a ray. I only got a mini-ray (laughs), once.

JD: (Laughs) So, I guess that means you are still with us, Peter. How would you explain your style on the vibraphone. I’ve seen people use many mallets on one hand, and some use one or two. What is your style, really?

PA: Well, I never sort of looked upon it, when I play, as a percussion instrument. I’ve always thought in the genre as a horn. You know I have pretty good technique as I play drums. The tendency of several people who played drums previously is to treat the instrument like a drum and show off their technique and play a lot of notes. I’ve never sort of looked at it that way. I love the timbre, the sound of the instrument. It’s a beautiful instrument. I read a book on psychology once and it’s supposed to be very good for the soul, which was quoted in the book and it is really because you get lovely sounds from the instrument. Also, you can get very good percussive swinging sound, which is the style I play in.

JD: Yes, and it’s very enjoyable. Peter, now I’m going to get to something neat, that’s happened recently. You have discovered some lost tapes of you and a who’s who of American jazz musicians and you put a CD out. Would you like to tell us about that?

PA: Yes, well I was working in Carnegie Hall with Benny (Goodman) one evening. He never had a steady sextet. I was probably the most steady and Bucky Pizzarelli was another one, as was John Bunch, but for this particular evening he acquired the services of Slam Stewart at the bass, Hank Jones at the piano, Zoot Sims at the tenor saxophone, Urbie Green on the trombone, Bobby Hackett on cornet and we had Grady Tate on drums.

Prior to the night he spoke to me about Grady Tate and I said, “Ya, I really like his playing.” He said, “Oh, I heard Connie Kay recently.” He was playing with the Modern Jazz Quartet. He said, “I really like him.” I said, “Well he’s great, but I really like Grady, too.” He said, “Tell you what, we’ll use two drummers (laughs). When you play you can have Grady Tate and when I play I can have Connie Kay.” By that he meant—I used to open for him and I did about ten minutes with the quartet and the rhythm section and that’s what he was referring to. Anyway the next night after the Carnegie Hall show I had a concert at Ontario Place in Toronto. It was a forum down on the water front and I asked all the guys that he hired if they were available that night. It so happens that they all were and I knew that this is only once in a lifetime that Benny Goodman would have these major people together, because individually they were so busy. So half way through the concert at Ontario Place it occurred to me that I should really find out if there was a recording studio available to record these guys, because they’ve all got to stay overnight. So I called up RCA, which had a studio then in Toronto and fortunately the engineer was available and the studio was available from 11 PM that night.

So after the concert we all went over to the studio and recorded until 3 AM and had a bottle of wine and some nice Chinese food, I guess it was. I had everyone play their favourite party piece and we did two or three other pieces as an ensemble. After it was all done I tried to contact somebody in England at a major record company. I was over there with the Goodman Sextet and unfortunately when we got to England I had an appointment about an hour after landing but the Benny Goodman people didn’t have the correct immigration papers so we were all held up at the airport. Now I have dual citizenship, British as well as Canadian. I could have left, but Goodman insisted I stay, so I missed the appointment with this guy at Philips Records and the next day we had to leave so that was it. So, I sort of shelved it for a while and then I saw another man who didn’t impress me very much, who was rather interested but didn’t show too much enthusiasm about Bobby Hackett. I said, “What?” Bobby Hackett was one of the most beautiful players of that instrument in the world. You know that ‘String of Pearls,” Jim? There’s a trumpet solo in the middle of the band that goes (hums the solo), that was Bobby Hackett. Glenn Miller hired him as a trumpet soloist and he didn’t need another trumpet, so he gave him a guitar and told him to strum away at it. So he sat there and was a very mediocre guitar player, but when there was anything in the way of a lyrical trumpet solo it was Bobby Hackett. Anyway, that didn’t work out, so I just sort of put it aside and didn’t bother with it and there was another problem which I won’t go into.

Recently I signed with a recording company and I told them about the record that I have, and Geoff (Kulawick), the CEO, said “Let’s give a listen to it.” And he did, and he was so impressed, so True North Records and Linus (Entertainment) put it out recently and we’ve had nothing but very glowing reviews. All of them have been five star quality and literally five stars; a classic record.

JD: I concur. It is wonderful. I like the fact that you left the out takes in. You can hear the engineer calling off the songs. You can hear the guys chatting and it just makes you feel like you were at that little studio with the red wine flowing and the Chinese food out and the people were just having fun. It’s just beautiful. I love it.

PA: Thanks for saying that. I’m very happy to know that because that was basically the reason why we did it. We spoke about it. Shall we leave it in? And Geoff thought as I did, we’ll keep it in. And it truly was a gem. All the little bits and pieces and some of the people that would know some of the voices, especially Zoot Sims, were very thrilled to hear it.

JD: That was a really good idea.

PA: Oh, thank you.

JD: Peter are you making any appearances in the near future?

PA: Yes, I am. As a matter of fact, we are going to play the Montreal Jazz Festival this year and the Edmonton, Toronto and Saskatoon Jazz Festivals. I go to Switzerland every year and play over there and also in England I’ll be doing some concerts.

JD: I just want to mention one more thing. I interviewed Carol McCartney a few years ago and you were on her wonderful CD A Night in Tunisia. I’ll tell you, she had nothing but nice things to say about you. Have you had a chance to play with her since then?

PA: Yes, as a matter of fact, we just made an album with nine of the leading girl singers in Canada. Carol McCartney, Carol Welsman, Sophie Milman, and Jackie Richardson—actually there was nine of them and they all did a piece and it was really wonderful. That is do to come out in about two or three months.

JD: I’m looking forward to hearing that. Thank you very much for speaking to me. I just love your stories and the CD is wonderful.

PA: Thanks for calling and I hope to meet you one day.

JD: Peter, that would be my pleasure.

Peter Appleyard and the Jazz Giants The Lost Sessions 1974

Available on iTunes, True North Record Store www.truenorthrecords.com

Jim Dupuis is the host of Jazz Notes, now in it’s 13th year on Wed. 5-7 PM PT at www.thex.ca

comments powered by Disqus